AI Red Teaming Has A Subspace Problem

Don’t buy, invest in, or pay for a course about “AI red teaming” until you read this | Part I | Edition 29

I’ve gotten threats over our newly released research in adversarial AI testing. I’m not going to stop this work.

You deserve to know the truth about adversarial AI.

So now, I’m going to tell you everything.

I’m going to lay out, in detail, exactly how to really attack AI. To do this, first I need to tell you what’s wrong with the status quo.

So I’m breaking down our new paper, “Quantifying the Risk of Transferred Black Box Attacks”, piece by piece.

Because I believe that whether you’re an investor, a buyer, or someone trying to learn this field for real, you have a right to know the truth.

Photo: Me circa 2019, exploring the theoretical bounds of adversarial subspaces & nuclear fauxhawks. Guess how many GPUs are in this photo?

Researchers at HiddenLayer recently published a vulnerability called EchoGram, where adding nonsense suffixes to prompts allows attacks to bypass guardrails with overwhelming success.

While the EchoGram attack looks new, it’s only hinting at the mathematics that attackers have been using to target AI systems in the wild for more than a decade.

What EchoGram definitely does reveal: The serious, intractable OPSEC problems that so-called “AI red teaming” both operates in, and creates. That is for another post.

For now, what’s important to note: These attacks haven’t changed.

And while EchoGram’s researchers used an elaborate system involving publicly available data to attack defensive systems, the real methods attackers use, and have used for ten years now, are far less difficult.

Why would adversarial attacks devised more than a decade ago work on today’s GenAI systems with such devastating efficacy?

Because of exactly what HiddenLayer’s public post doesn’t say.

The blog post comes very close to stating what is really at play in these attacks: The adversarial subspace problem.

Why haven’t the model providers like Google, Anthropic, and OpenAI responded to the disclosure?

Because they know the same thing that real AI hackers know: The subspace problem isn’t fixable.

Machines Don’t Read

When you enter a prompt into an LLM-based system, the model itself never sees what you wrote.

Instead, your prompt is translated into a mathematical representation that AI can understand.

It does not read the prompt, because machines can’t read.

AI is just software. Software run by computers, which still do not ‘understand’ natural language.

They can model it, and even represent its relationships well sometimes mathematically. But they can never understand it. At least not in this iteration of LLM-based AI.

That’s why they’re called language models, not language understanders.

These mathematical representations of the text you write are not perfect. They are not 1:1 inputs and outputs.

Anyone who has ever worked with translation of one natural (human) language to another knows that even when trying to equate words or phrases in different languages, there is rarely a 1:1 direct correlation.

And translating natural language into machine math is no different.

This, by the way, is a feature and not a bug for LLM systems, because they weren’t originally designed for conversation–they were designed for translation.

In this domain, it makes perfect sense to add numerical representations in the middle when moving between languages. Just add more context, and (rough) translation starts to be possible.

That’s why they said “attention is all you need”. For the translation use case, that’s correct.

So why does this matter?

Because machines have their own language, and it’s based on numbers.

Speaking To Machines: Numerical Translation

What this number-translation process is all meant to do: Extract meaning from text.

Humans do this naturally, because we have human experiences with the world.

A machine can’t. So the closest researchers have come to bridging this gap is to approximate numerical equivalents of meaning.

The key word here: Approximate.

Meaning will always be subjective, as it’s encoded in a much higher dimensional space than just language alone–it’s context, personality, experience, emotion.

A model flattens all these to a string of numbers.

And anytime you flatten something into a lower dimensional space, you create an attack vector.

Here’s how it works.

Compounding Linguistic Imprecisions, Compounding Attack Vectors

Language is imprecise. Notoriously so. Encoding it into numbers adds another layer of imprecision–not just because meaning is lost, but also because meanings overlap.

This results in imprecision in the numerical representations too.

Let’s take a hypothetical prompt. This consists of a string of words or other symbols, which are translated into number representations for the machine.

Because of both the flattened imprecision, and the overlap among words & concepts, there could be many prompt strings which would result in a similar numerical representation.

How many? We don’t know.

The search space is very large.

Think about it like this: How many different ways can you think of to say the same idea in your first language? Depending on the idea you choose, probably a lot.

Now add in all the other human languages–you now have many, many ways to convey the same idea.

Now imagine that none of this matters, because it’s all going to be translated into numbers anyway. If the goal of the numerical translation is to capture meaning, the core idea, you can easily see how multiple turns of phrase could all result in similar numerical representations.

If we expand this concept, we realize that the words themselves don’t matter at all–it’s the meaning encoded in the machine’s number language that matters.

So to get to the same number translation, we could use many, many sentences, in many, many languages–or no words at all.

In fact, combinations of symbols or numbers could in theory produce the same string of numbers as the beautiful idea you expressed so poetically in your native language.

What this means:

The prompt you typed is pointless.

There are likely a number of strings that could in theory produce the same exact result.

And similarly, a nearly infinite number of attacks.

The Subspace Problem

Every prompt has, in theory, a set of character groups that will satisfy the requirements to achieve a similar numerical representation (at some threshold of similarity).

What this means: Once you decide how similar you need the numerical representation to be, you can search for equivalents. Or engineer them.

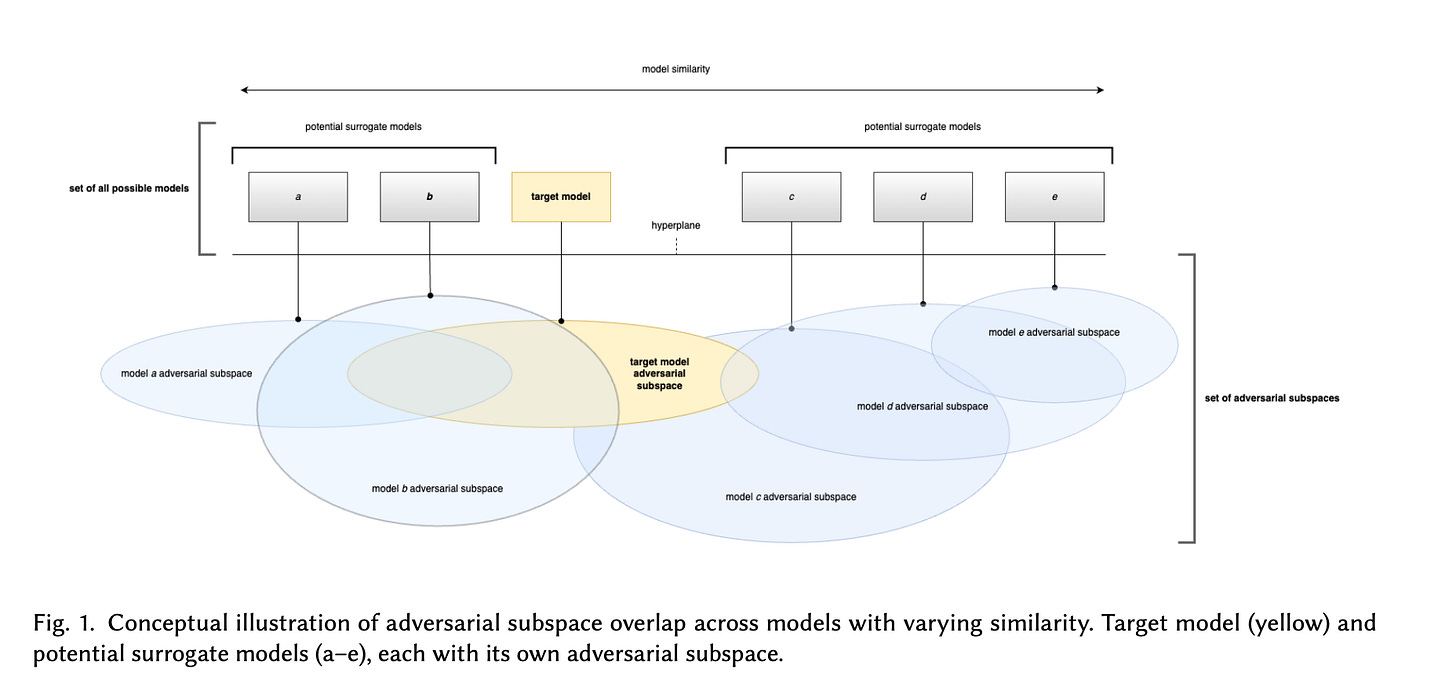

Similarly, every AIML model, in theory, has a set of adversarial attacks that will be effective against it.

It’s more of a space–you can think of it like a box that holds all the effective attacks against a particular model.

And these boxes are massive, with all evidence indicating that they are far too large for search to be computationally feasible.

Illustration of adversarial subspaces. Source is our new paper, which sets the SOTA for adversarial testing.

Thousands of natural language prompts may be just a drop in an ocean of possible attacks. One slight iteration, one tiny round of perturbations, and an old, “defended” attack becomes new.

This is why the tiny changes in the EchoGram attack returned such powerful effectiveness. Now imagine how many potential tiny changes might possibly exist: Across languages, character types, numbers, symbols, and more.

Meaning: You will never find all the attacks.

A library of natural language prompts is meaningless.

Unless you’re trying to spot the (literal) AI script kiddies.

Stay frosty.

Next up: AI Red Teaming Has An OPSEC Problem.

The Threat Model

Adversarial subspaces have been known to be large and overlapping since at least 2017, and more likely 2015, when well-known researchers published on this in highly cited works.

The adversarial subspace problem is a mathematical feature of these systems; it cannot be patched.

Known mathematics nearly a decade old mean that attackers certainly have known about these subspaces for years.

It would seem that the only ones who didn’t know are people who self-styled as “AI red teams”.

Resources To Go Deeper

Ian J. Goodfellow, Jonathon Shlens, and Christian Szegedy. 2015. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. arXiv:1412.6572 [stat.ML]

Florian Tramèr, Nicolas Papernot, Ian Goodfellow, Dan Boneh, and Patrick McDaniel. 2017. The Space of Transferable Adversarial Examples. arXiv:1704.03453 [cs, stat]

Hu Ding, Fan Yang, and Jiawei Huang. 2020. Defending Support Vector Machines against Poisoning Attacks: the Hardness and Algorithm. arXiv:2006.07757 https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.07757

Niklas Bunzel, Raphael Antonius Frick, Gerrit Klause, Aino Schwarte, and Jonas Honermann. 2024. Signals Are All You Need: Detecting and Mitigating Digital and Real-World Adversarial Patches Using Signal-Based Features. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Workshop on Secure and Trustworthy Deep Learning Systems. 24–34.

Executive Analysis, Research, & Talking Points

The Recipe For Agentic AI Red Teaming - And How To Spot Who Is Legit

If you think real attackers in real life maintain repos of prompts–no, they do not.

Why would they? When numbers work faster, are more iterable, and the experiments easily more repeatable?

The recipe was never the prompts–the secret sauce is the processes attackers develop to mathematically, and repeatedly, perturb any input into an attack set. EchoGram came close.

Here’s how it really works: